MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

The presidential re-election syndrome torments Latinamerica

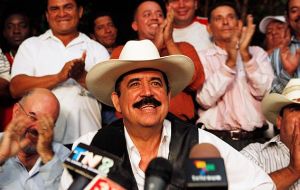

Honduras Manuel Zelaya allegedly ousted for his re-election plans

Honduras Manuel Zelaya allegedly ousted for his re-election plans Presidential re-election has become a controversial issue in Latinamerican politics and some of the latest incidents are regional headlines including the current upheaval in Honduras which remains unsolved and can be traced to ousted President Manuel Zelaya alleged re-election bid.

Currently 13 out of 18 democracies in Latinamerica allow some form of re-election, consecutive or non consecutive, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Panama, Dominican Republic, Peru, Venezuela and Uruguay.

Three countries ban presidents from any form of re-election under any circumstances, Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras.

This is precisely the argument of the interim Honduran government, which was instated in agreement with the Legislative, Judicial branches, and the military, to replace ousted Zelaya for his attempts to begin a re-election process.

According to Article 239 from the Honduran constitution the president can be punished with his ousting even when “proposing a re-election bid”.

Another case in the headlines is Colombia’s Alvaro Uribe, still not openly declared, but which already has partial congressional approval for a third consecutive mandate. Uribe is currently in the last leg of his second term, following a constitutional amendment which enabled his re-election in 2006.

President Uribe is one of the leaders with highest public opinion support in the region based on his strong-hand policies towards drug trafficking cartels and terrorist practices from the FARC rebel groups, --allied with the drug trade-- and which when he took office controlled almost a third of the country’s territory.

If Congress this week approves the amendments the proposal would be then considered in a national referendum which he can be expected to win.

However the Judicial can still bar the initiative because of an ongoing investigation into irregularities committed when the first re-election amendment was voted in Congress in 2005.

The recent contagion of Latinamerican democratic leaders to remain in power can be traced to the nineties with the examples of Argentina’s Carlos Menem (1989/1999), Peruvian Alberto Fujimori (1990/2000) and Brazil’s Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1994/2002).

Closer in time is Venezuela’s populist Hugo Chavez who taking advantage of his first landslide victories managed full control of the Legislative, drafted a new “Bolivarian” constitution, was re-elected for another six years in 2006.

In December 2007 the Venezuelan electorate rejected a referendum which proposed another constitutional reform including unlimited presidential re-election.

However in February this year a new referendum but limited to the indefinite re-election of all elected posts was finally approved.

Two Chavez allies also joined the bandwagon: Evo Morales from Bolivia and Rafael Correa from Ecuador managed at the height of their power to amend the constitution and have re-election approved, although for an only mandate.

Correa was re-elected on the new rules earlier this year and Morales faces a similar test next December, when he’s expected to win.

Another leader, satellite from Venezuela, Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega is in the same process having launched the initiative last July in coincidence with the 30th anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution. He could very well also achieve his goal according to local political analysts.

Argentina’s Carlos Menem re-election initiative was approved by a constitutional assembly in 1994 following an agreement with the opposition. However his attempt of a third re-election never prospered and was based on the endemic “lame duck syndrome” faced by all Argentine presidents since the return of democracy in 1983, including currently the Kirchners.

Peru’s Fujimori who was formally elected in 1990, later closed Congress with support from the Army and had a new constitution, including re-election, approved in 1993. He was re-elected in 1995 and in 2000 argued that he had the right to another term based on the new constitution. This was disputed and corruption, human rights abuses and political scandals put an end to his career. He fled to Japan.

Brazil’s Cardoso was elected in 1994 for a four year period but had the constitution amended for an only second consecutive term and was confirmed in 1998, basically to implement the continuation of a successful financial stabilization program.

However given Brazil’s imperial past (when the Portuguese Crown, compliment of the Royal Navy, took refuge in Brazil from the advancing Napoleon forces) he has been crystal clear that one additional term in enough, a second additional would be in his own words “imperial”.

Current President Lula da Silva, one of the most popular in recent Brazilian history, has also communicated this message to his followers.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rules-

Read all commentsFancy having governments who actually carry out the promises they make at election time, confident that the majorities of their electorates will vote them in again in internationally recognised free and fair elections.

Aug 26th, 2009 - 05:57 am 0Whatever next.

Commenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!