MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

Brief history of the Falklands since first references in the 16th century to 1841

The presentation of the booklet of “Our Islands, Our History”

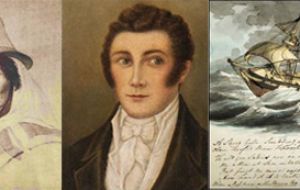

The presentation of the booklet of “Our Islands, Our History”  John Davis, Dutch explorer Sebald de Weert and French nobleman Louis Antoine de Bougainville

John Davis, Dutch explorer Sebald de Weert and French nobleman Louis Antoine de Bougainville  Gaucho Antonio Rivero, Louis Vernet and Captain Onslow of HMS Clio

Gaucho Antonio Rivero, Louis Vernet and Captain Onslow of HMS ClioThe Falkland Islands, lying about 560km off the mainland of South America, comprise two large islands, East and West Falkland, and a swarm of other islands ranging from substantial ones off the western edge of West Falkland to smaller islets and reefs scattered all along the coasts.

Who first discovered these Islands is a mystery. Parties of Patagonian Indians may have been blown across from the mainland and some stone tools have been found on Falklands shores. Two maps in the archives in Paris and Istanbul from the early sixteenth century which appear to represent the Islands have a Portuguese connection. But the first recorded sighting of the Falkland Islands was by the English explorer John Davis who in August 1592 was blown by a storm into ‘certaine Isles never before discovered’. Davis’ account was published in 1600 in London by Richard Hakluyt.

Davis was followed by the English seaman Sir Richard Hawkins in 1594 and the Dutch explorer Sebald de Weert who visited in January 1600. The first recorded landing on the uninhabited islands took place on West Falkland on 27 January 1690, when the English sea captain John Strong came ashore.

Strong named the passage between the two Islands ‘Falkland’s Sound’ and Lord Falkland’s name later became attached to the entire main Islands group. In the early eighteenth century French sailors from the port of St Malo gave their name to ‘Les Iles Malouines’.

More than half a century later, in the 1760s, two settlements were established in East and West Falkland almost simultaneously by two different countries.

The French nobleman Louis Antoine de Bougainville, in a brief chapter of his remarkable life, landed settlers who had left Nova Scotia after the British conquest of French Canada at Port Louis in East Falkland in 1764. In January 1765 Admiral Byron landed at Saunders Island north of West Falkland and claimed the isles for the crown of Great Britain.

A second British expedition in 1766 returned to Saunders and named their settlement Port Egmont. They built houses and a prefabricated blockhouse and planted gardens. Although British and French colonists became aware of each other’s activities relations were polite, helped no doubt by the distance between Port Louis and Saunders Island.

But in 1767 Bougainville was obliged to sell his settlement to the Spanish crown, which resented a foreign colony in what it considered its sphere of influence. The Spaniards took over Port Louis which they named Puerto de la Soledad. Keen to assert their authority, a Spanish fleet arrived at Saunders Island in 1770 and obliged the small British garrison to leave. An international crisis followed, which was only resolved in 1771 when Spain agreed that the British settlement should be restored and three ships sailed out to re-establish British authority in September 1771.

It was short lived because in 1774 the government in London decided to withdraw their settlement on grounds of economy. The garrison left in May of that year, leaving behind a lead plaque asserting British sovereignty.

The Spanish garrison remained on East Falkland until 1811 when, under pressure of French invasion at home and revolutions in its South American empire, Spain withdrew its force, also leaving a plaque asserting its sovereignty.

During the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century the Islands were the centre of a lucrative whaling and sealing trade undertaken by sailors from New England, Britain and France. The whalers camped on outlying islands, particularly New Island, slaughtering cattle and geese for provisions, repairing their ships and ‘trying’ (rendering down), seal, sea lion, whale and penguin carcasses for oil.

In 1820 a Buenos Aires privateering ship, under the command of David Jewett, who was from the United States but was commissioned as a colonel in the Buenos Aires navy, put into Port Louis.

Jewett, on his own initiative, for no instructions have ever been found, claimed the Islands for the United Provinces (of Buenos Aires). He then sailed away and it was not until November 1821 that news came to Buenos Aires, via foreign newspaper reports, that Jewett had made this claim.

In the mid-1820s Louis Vernet, from a French Huguenot family, born in Hamburg and living in Buenos Aires organised expeditions to the Islands. The first in 1824 was a disaster, but a second in 1826 was better organised and Vernet founded a successful settlement at Port Louis on the site of the Spanish colony.

In 1829 he was appointed commandant of the settlement by the government in Buenos Aires. However Vernet over-reached himself when he confiscated ships owned by United States sealers on the grounds that they were poaching. As Americans had been sealing and whaling in Falklands waters since the 1770s they were outraged and a naval frigate, the USS Lexington, sailed to Port Louis in December 1831, dismantled Vernet’s defences and took away most of the Europeans among his settlers.

Ten months later, in October 1832 the Argentine government sent a garrison to Port Louis who promptly mutinied and murdered their commander.

The British had been watching events closely as Vernet set up his colony and their diplomatic mission in Buenos Aires had protested at Vernet’s appointment and again when the new ill-fated garrison commander was appointed in 1832.

London was concerned that the Falklands would descend into anarchy and become a base for pirates. In 1832 Captain Onslow of HMS Clio was instructed to reassert British sovereignty over the Islands, but without expelling the civil population.

He arrived at Port Louis on 2 January 1833.

On the following morning in a firm but tactful manner, Onslow instructed the Argentine naval schooner whose captain had taken charge at Port Louis to leave. No shots were fired; there was no violence of any kind.

Four civilians chose to leave with the mutinous garrison in the schooner but the majority of Vernet’s two dozen settlers, mostly gauchos, remained under the British flag.

Onslow made no provision for the administration of the Islands beyond giving the Irish storekeeper a Union Jack and 25 fathoms of rope to fly it with. Charles Darwin, who visited with Captain Fitzroy in the Beagle in March 1833, described the storekeeper as the ‘English resident’.

Vernet, who was still administering his property from Buenos Aires, was the unwitting cause of shocking events in August 1833 when the gauchos, led by Antonio Rivero, turned on and killed his agents in Port Louis (including the storekeeper) in protest against Vernet’s refusal to pay them in hard currency.

A small British party led by a naval lieutenant, Henry Smith, was landed in January 1834, restored order and arrested the murderers. They were sent to England for trial; however as only British subjects could be tried in Britain for homicides committed outside the British Isles they were returned to Montevideo.

For the next eight years the Islands were administered by a succession of naval lieutenants who reported to the Admiralty, keeping a log of events as though they were on ship and always remembering to record the weather. The population of Port Louis slowly grew under British rule and a British ship conducted the first careful survey of the Falklands’ coasts.

In 1841 the government in London decided to regularise the situation and despatched a young engineer officer Richard Moody to the Islands as lieutenant-governor.

(From “Our Islands, Our History”, an official booklet from the Falkland Islands Museum and National Trust)

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rules-

-

-

Read all commentsBrief Fairy Tails?

Jan 03rd, 2013 - 06:50 pm 0Truth hurt?

Jan 03rd, 2013 - 06:54 pm 0@1 And yet all more believable than any Argentine argument.

Jan 03rd, 2013 - 07:01 pm 0Commenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!