MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

Latam’s cash transfer programs have proven more effective in combating poverty

Leonardo Gasparini elaborated the report La Plata University CEDLAS

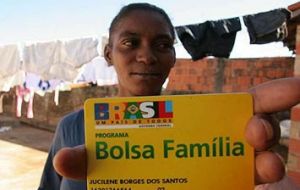

Leonardo Gasparini elaborated the report La Plata University CEDLAS  Brazil’s family allowance is the largest program covering 52 million out of a population of 198 million

Brazil’s family allowance is the largest program covering 52 million out of a population of 198 million Latin America’s cash transfer programs are a more effective weapon against poverty and social inequality than economic growth alone, according to a study by two local economists.

In 2010, these social programs operated in 18 countries, reaching 19% of the region’s approximately 600 million people and achieving “a substantial reduction in extreme poverty and a significant fall in inequality,” according to the study published by the Centre for Distributive, Labour and Social Studies (CEDLAS) of the National University of La Plata, Argentina.

The report, Social policies to reduce inequality and poverty in Latin America and the Caribbean, by Leonardo Gasparini and Guillermo Cruces, reviews regional programs for income transfer to the poorest of the poor and recommends expanding them in order to eradicate extreme poverty.

Gasparini and Cruces, CEDLAS’ director and deputy director, respectively say that non-contributory programs “was the main innovation” in social policies in the region over the last decade.

“Cash transfer plans are very useful instruments as part of an overall strategy for reducing poverty and inequality,” Gasparini said. “They are relatively easy to implement, administer and monitor, and they have a direct impact on the beneficiaries’ quality of life.”

Gasparini highlighted the advantages of the conditions attached to the payments, which provide “an incentive for certain behaviours, such as encouraging school attendance by children and teenagers, and more regular health checks.” While “they are not a complete solution to the serious problem of income distribution, their importance should not be underrated,” he said.

According to the study, published in March, even in a scenario of sustained economic growth, programs like Argentina’s universal child allowance (Asignación Universal por Hijo) and Brazil’s family allowance programme (Bolsa Família) “play an essential role in achieving improved distribution.”

“The region cannot depend solely on economic growth, even if there is full employment, because social protection is also needed,” the study says.

The plans, while different in format, aim to provide a monthly transfer from state coffers to low-income families or elderly people who worked in the informal economy and do not draw pensions. The family plans usually require school attendance and health checks for children under 18.

Ecuador’s human development voucher (Bono de Desarrollo Humano) has the widest coverage, benefiting 44% of the country’s total population. But Brazil’s family allowance is the largest program in absolute terms, covering 52 million of the country’s 198 million people.

The least effective plan appears to be Mexico’s Oportunidades, judging by the rise in poverty, which affected 53.3 million of the country’s 118 million people at the end of 2012, according to the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL). Given these results, the government is reviewing the programme.

“The basic weakness is the concept that the problem of poverty is due to a lack of skills, and that the main focus must be on funding capacity building,” said Clara Jusidman, honorary president of Incide Social, an NGO in Mexico.

Created in the late 1990s, Oportunidades, which took on its current form in 2002, has a 2013 budget of over five billion dollars and aims to benefit 5.8 million families. The family allowance is conditional on children and teenagers staying in school and attending health checks.

According to Jusidman, “under this plan, human rights have been violated and people have been excluded, and the state takes a paternalistic attitude.”

Gasparini and Cruces pointed out that in the 1990s, the region’s economic growth was associated with greater inequality. In contrast, since the turn of the century, cash transfer programmes have contributed to an acceleration of the reduction of poverty, especially extreme poverty.

The proportion of people living on less than 2.5 dollars a day shrank from 27.8% of the population of Latin America in 1992 to 24.9% in 2003, 16.3% in 2009 and 14.2% in 2010, the study says. It recommends expanding coverage to bolster the impact of the programmes over a shorter time span.

“In several countries, the beneficiary base is still small and in others the amounts involved are trifling. There is room to expand these programmes,” Gasparini said. However, he did not think universal coverage was necessary.

The study observes that, with slower growth, fighting poverty takes longer. For instance, if per capita GDP grows at an average of 2% a year, 5.5% of the population will be living in extreme poverty in 2025, while if growth stands at four percent, less than three percent of the population will be extremely poor by that year.

In contrast, with an “additional fiscal effort of 0.5%” of GDP for these social programs, the region would achieve the same poverty reduction 10 years earlier, in 2015.

Based on the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC’s) figures for 2010, the region spent an average of 0.4% of GDP on cash transfer programs. According to the authors, some countries could increase their efforts, in line with the study’s recommendations, while others may have to take out external loans.

The countries that will need most aid are those where a high proportion of the population is in the informal economy and therefore lacks health and retirement coverage — such as Bolivia, Ecuador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay and Peru.

“Bolivia, Nicaragua and Guatemala need foreign assistance for programs to cover the proportion of their population living in extreme poverty,” Gasparini said. The other countries have the resources to finance these programs, and even to expand them”.

The head of CEDLAS said the current average expenditure seemed relatively small compared with other subsidies that benefit the middle and upper classes. He added that while these programmes are sometimes criticised, “there is broad social support in most countries and very few candidates to elected posts in the region openly call for their elimination.”

Gasparini said, however, that support for the programmes “does not negate the fact they may have undesirable features, such as slowing down the rate of formalisation of the economy, or effects on the supply of labour, which need more serious work.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rules-

-

-

Read all commentsOH DEAR! Argie “economists” getting all confused about what they are supposed to be doing.

Sep 16th, 2013 - 02:49 pm 0““Cash transfer plans are very useful instruments as part of an overall strategy for reducing poverty and inequality,” Gasparini said. “They are relatively easy to implement, administer and monitor, and they have a direct impact on the beneficiaries’ quality of life.””

In other words, we take money off people who have got it and give the those who don’t have it. But this little gem is an exercise in talking bollocks:

““The region cannot depend solely on economic growth, even if there is full employment, because social protection is also needed,” the study says.” WHY?

Either (in FULL employment) the pay is insufficient to cover the costs of living:

OR there are some lazy bastards who DO NOT WANT TO WORK.

The Brits are used to this crap under New Labour who paid “family credits” in an uncontrolled way. Even some people with a family income equivalent to USD 80,000 got some money from the state that they never had to pay back!

BUT, this argie concept doesn’t work! Not if you look at Mexico:

““The basic weakness is the concept that the problem of poverty is due to a lack of skills, and that the main focus must be on funding capacity building,” said Clara Jusidman, honorary president of Incide Social, an NGO in Mexico.”

In other words, we have provided more jobs but there are still MORE people in poverty. There is a blindingly obvious reason for this. Why would they work when you give them money NOT TO!

But all is not lost!

“Gasparini said, however, that support for the programmes “does not negate the fact they may have undesirable features, such as slowing down the rate of formalisation of the economy, or effects on the supply of labour, which need more serious work.”

A statement of the bleeding obvious! These so called “economists” must have gone to the same school as TMBOA, they have the same idiocy at work. That’s the argie “model” concept for you.

Make it voluntary-the cash transfers on both sides, have brilliant people incentivize success in everyone's life. MANY of the most great institutions in the U.S. have benefitted from gifts- Stanford, Central Park, etc. I am glad some of the support in LatAm is raising people, not just institutions up.

Sep 16th, 2013 - 09:29 pm 02 Ayayay

Sep 17th, 2013 - 11:57 am 0You are missing the point here.

They are giving the money to the poor because the system cannot be arsed to provide them with an education and jobs.

Gifting money to universities is an INVESTMENT in the future of young people and the world in general. Totally and diametrically opposite to each other.

Commenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!