MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

Why America invented Ahmad Chalabi

Chalabi was less a cause of the Iraq war than a convenient enabler of it. He was an answer to US’s problems, not Iraq’s

Chalabi was less a cause of the Iraq war than a convenient enabler of it. He was an answer to US’s problems, not Iraq’s  George W. Bush was determined to repudiate Iraq policies of both presidents Clinton and his father, and stocked his administration with backers of Chalabi.

George W. Bush was determined to repudiate Iraq policies of both presidents Clinton and his father, and stocked his administration with backers of Chalabi.  Then came 9/11. Having banged on about the dangers of Iraq for years, the Bush administration decided to take on Hussein once Afghanistan was done.

Then came 9/11. Having banged on about the dangers of Iraq for years, the Bush administration decided to take on Hussein once Afghanistan was done.  Left unattended, Iraq started to unravel. The lack of postwar planning did its damage: Iraq spiraled into chaos from which it has never fully recovered.

Left unattended, Iraq started to unravel. The lack of postwar planning did its damage: Iraq spiraled into chaos from which it has never fully recovered. The following piece by Gideon Rose (*) was published in The New York Times Opinion page and helps to understand much about the Iraq war and ongoing instability.

With his death, the Iraqi politician Ahmad Chalabi is once again in the news. Detractors rage about his supply of fabricated intelligence on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction that supposedly tricked Washington into war. Supporters claim he was a heroic dissident who was never given the chance to transform his troubled country into paradise.

Both miss the real story, which is that Mr. Chalabi was less a cause of the Iraq war than a convenient enabler of it. He was an answer to America’s problems, not Iraq’s, and if he had never existed, his backers would probably have conjured up a replacement to serve the same function.

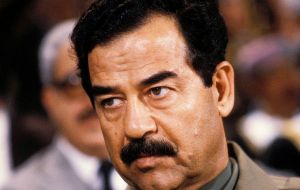

Ever since the United States assumed responsibility for securing the energy-rich Persian Gulf in 1980, it has faced a challenge: how to protect the weaker countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council from the stronger dictatorships to the north, Iraq and Iran. When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, the situation became acute, and Washington committed itself to pushing his forces back — as the gulf war achieved the next year.

Once Kuwait was freed, however, the administration of President George H. W. Bush remained stuck with the original problem of protecting the G.C.C. from future attacks. Nobody wanted to go on to Baghdad and defang Iraq, but neither did anyone want to keep a large, permanent garrison in the gulf like the one the United States maintains in South Korea.

So the administration invented a third option, convincing itself that some unknown Iraqi military figure would oust Mr. Hussein after he’d lost the war, maintain order and serve as one more reliable authoritarian ally in the region. But no such figure emerged, Mr. Hussein managed to suppress postwar uprisings and Washington grudgingly backed into the Korean-style commitment it had sought to avoid.

The Clinton administration inherited this policy and maintained it for another eight years. But containment had obvious downsides: It was costly, risky, played for a draw rather than a win, and contributed to terrible suffering among the Iraqi people. So Republicans, and even some Democrats, kept clamoring for an alternative — though, of course, one that didn’t involve the even worse options of letting Mr. Hussein loose or colonizing Iraq.

Enter Mr. Chalabi, offering a solution. With only a little help, he promised, his band of Iraqi exiles could solve all our problems. They would start a rolling insurrection, gather strength as oppressed Iraqis flocked to their banners, get rid of Mr. Hussein and set up a new government that would be democratic, capitalist, pro-American and even pro-Israel.

This offer was too good to be true. In fact, professionals throughout the United States national security bureaucracies held it, and Mr. Chalabi, in contempt. (As Gen. Anthony C. Zinni, then head of the Central Command, put it in 2000, recalling the Bay of Pigs fiasco, the exiles were promising “pie in the sky. They’re going to lead us to a Bay of Goats.”)

But Mr. Chalabi was clever. He told critics of the administration what they wanted to hear: You can get rid of containment and Mr. Hussein with almost no cost, effort or future commitment. Like gullible infomercial viewers, his American supporters couldn’t resist the pitch.

When George W. Bush took office, he was determined to repudiate the Iraq policies of both President Clinton and his father, and stocked the senior levels of his administration with backers of Mr. Chalabi. Then came 9/11. Having banged on about the dangers of Iraq for years, and having convinced themselves that those dangers could be eliminated cheaply and easily, Bush administration officials decided to take on Mr. Hussein once Afghanistan was done.

The American military refused to go along with the Iraqi exiles’ ludicrous plans for a rolling insurrection, insisting on the surer path of a direct invasion. Yet nobody in Washington, either military or civilian, wanted the responsibility of governing Iraq once Mr. Hussein was gone, so that task was not assigned. The details would be worked out later (possibly including a role for Mr. Chalabi).

Everyone knows the result: Left unattended, Iraq started to unravel. Panicked, the Bush administration improvised an occupation under the Coalition Provisional Authority, with L. Paul Bremer III as proconsul. But the administration’s “light footprint” strategy and lack of postwar planning had done their damage: The country spiraled into chaos from which it has never fully recovered.

So put aside the dubious W.M.D. intelligence (it wasn’t all Mr. Chalabi’s fault), and forget the fantasies that Mr. Chalabi could have been Iraq’s George Washington. Mr. Chalabi’s role was as a huckster who peddled magical thinking by assuring American policy makers that they could have it all and didn’t need to make the hard choices that real-world foreign policy actually involve.

Mr. Chalabi may no longer be around, but others like him are. And unfortunately, new suckers are born every minute.

(*) Gideon Rose is the editor of Foreign Affairs and the author of “How Wars End”

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rulesCommenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!