MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

UN acknowledges role in the Haiti imported cholera epidemic that killed thousands

”UN has become convinced that it needs to do much more regarding its own involvement in the initial outbreak and the suffering of those affected by cholera.”

”UN has become convinced that it needs to do much more regarding its own involvement in the initial outbreak and the suffering of those affected by cholera.”  The statement comes on the heels of a confidential report sent to Mr. Ban by a longtime United Nations adviser Philip Alston, New York University law professor

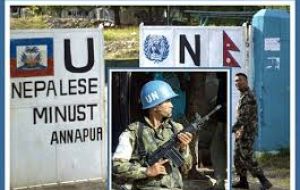

The statement comes on the heels of a confidential report sent to Mr. Ban by a longtime United Nations adviser Philip Alston, New York University law professor  The first victims lived near a base housing 454 United Nations peacekeepers freshly arrived from Nepal, where a cholera outbreak was underway

The first victims lived near a base housing 454 United Nations peacekeepers freshly arrived from Nepal, where a cholera outbreak was underway  Numerous scientists have since argued that the base was the only plausible source of the outbreak, whose real death toll could be much higher than official numbers

Numerous scientists have since argued that the base was the only plausible source of the outbreak, whose real death toll could be much higher than official numbers  Mr. Alston wrote that the United Nations’ Haiti cholera policy “is morally unconscionable, legally indefensible and politically self-defeating.”

Mr. Alston wrote that the United Nations’ Haiti cholera policy “is morally unconscionable, legally indefensible and politically self-defeating.”  UN denial “upholds a double standard according to which UN insists that member states respect human rights, while rejecting any such responsibility for itself.”

UN denial “upholds a double standard according to which UN insists that member states respect human rights, while rejecting any such responsibility for itself.” For the first time since a cholera epidemic believed to be imported by the United Nations peacekeepers began killing thousands of Haitians nearly six years ago, the office of Secretary General Ban Ki-moon has acknowledged that the United Nations played a role in the initial outbreak and that a “significant new set of U.N. actions” will be needed to respond to the crisis.

The deputy spokesman for the secretary general, Farhan Haq, said in an email this week that “over the past year, the U.N. has become convinced that it needs to do much more regarding its own involvement in the initial outbreak and the suffering of those affected by cholera.” He added that a “new response will be presented publicly within the next two months, once it has been fully elaborated, agreed with the Haitian authorities and discussed with member states.”

The statement comes on the heels of a confidential report sent to Mr. Ban by a longtime United Nations adviser on Aug. 8. Written by Philip Alston, a New York University law professor who serves as one of a few dozen experts, known as special rapporteurs, who advise the organization on human rights issues, the draft language stated plainly that the epidemic “would not have broken out but for the actions of the United Nations.”

The secretary general’s acknowledgment, by contrast, stopped short of saying that the United Nations specifically caused the epidemic. Nor does it indicate a change in the organization’s legal position that it is absolutely immune from legal actions, including a federal lawsuit brought in the United States on behalf of cholera victims seeking billions in damages stemming from the Haiti crisis.

Anyhow it represents a significant shift after more than five years of high-level denial of any involvement or responsibility of the United Nations in the outbreak, which has killed at least 10,000 people and sickened hundreds of thousands. Cholera victims suffer from dehydration caused by severe diarrhea or vomiting.

Special rapporteurs’ reports are technically independent guidance, which the United Nations can accept or reject. United Nations officials have until the end of this week to respond to the report, which will then go through revisions, but the statement suggests a new receptivity to its criticism.

In the 19-page report, obtained from an official who had access, Mr. Alston took issue with the United Nations’ public handling of the outbreak, which was first documented in mid-October 2010, shortly after people living along the Meille River began dying from the disease.

The first victims lived near a base housing 454 United Nations peacekeepers freshly arrived from Nepal, where a cholera outbreak was underway, and waste from the base often leaked into the river. Numerous scientists have since argued that the base was the only plausible source of the outbreak — whose real death toll, one study found, could be much higher than the official numbers state — but United Nations officials have consistently insisted that its origins remain up for debate.

Mr. Alston wrote that the United Nations’ Haiti cholera policy “is morally unconscionable, legally indefensible and politically self-defeating.” He added, “It is also entirely unnecessary.” The organization’s continuing denial and refusal to make reparations to the victims, he argued, “upholds a double standard according to which the U.N. insists that member states respect human rights, while rejecting any such responsibility for itself.”

He said, “It provides highly combustible fuel for those who claim that U.N. peacekeeping operations trample on the rights of those being protected, and it undermines both the U.N.’s overall credibility and the integrity of the Office of the Secretary-General.”

Mr. Alston went beyond criticizing the Department of Peacekeeping Operations to blame the entire United Nations system. “As the magnitude of the disaster became known, key international officials carefully avoided acknowledging that the outbreak had resulted from discharges from the camp,” he noted.

His most severe criticism was reserved for the organization’s Office of Legal Affairs, whose advice, he wrote, “has been permitted to override all of the other considerations that militate so powerfully in favor of seeking a constructive and just solution.” Its interpretations, he said, have “trumped the rule of law.”

But it represents a significant shift after more than five years of high-level denial of any involvement or responsibility of the United Nations in the outbreak, which has killed at least 10,000 people and sickened hundreds of thousands. Cholera victims suffer from dehydration caused by severe diarrhea or vomiting.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rules-

-

-

Read all commentsTo little, to late,.

Aug 20th, 2016 - 07:24 pm 01 American: *too little, too late

Aug 20th, 2016 - 08:02 pm 0Puts a whole new meaning on “don't worry, we've come to help you”.

Aug 22nd, 2016 - 12:39 pm 0Commenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!