MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

Nobel Peace Price Winner Archbishop Tutu dies aged 90

Tutu had also opposed tribal initiation rites which caused deaths and mutilations

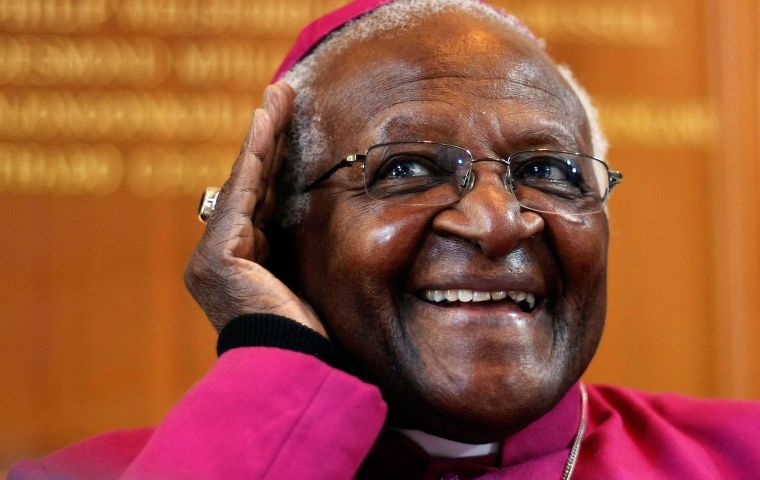

Tutu had also opposed tribal initiation rites which caused deaths and mutilations South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, an iconic figure during the country's fight against apartheid, has died Sunday at the age of 90 in Cape Town, it was reported. Tutu is survived by his wife of 66 years and their four children.

“Typically he turned his own misfortune into a teaching opportunity to raise awareness and reduce the suffering of others,” said the Tutu trust’s statement. “He wanted the world to know that he had prostate cancer, and that the sooner it is detected the better the chance of managing it.”

In recent years he and his wife, Leah, lived in a retirement community outside Cape Town.

Tutu’s death “is another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa,” South African President Cyril Ramaphosa said in a statement.

“From the pavements of resistance in South Africa to the pulpits of the world’s great cathedrals and places of worship, and the prestigious setting of the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony, the Arch distinguished himself as a non-sectarian, inclusive champion of universal human rights,” he added.

Tutu's funeral will take place Jan. 1 at the Cathedral of St. George in Cape Town, his former parish, and will close a week of events and acts of mourning.

The clergyman, known as “the voice of the voiceless”, was born in 1931 in Klerksdorp, a small town southwest of Johannesburg. The son of a domestic worker, Aletta Tutu, and a teacher, Zachariah Tutu, in 1953 he graduated from teaching and in 1958 he entered St. Peter's Theological College in Rosettenville to train as a priest.

In 1967, Desmond Mpilo Tutu became a chaplain at the University of Fort Hare. He then lived in the small African kingdom of Lesotho and in Great Britain, before returning to his country in 1975, where he actively fought against racial segregation. That same year, he was appointed dean of the Anglican cathedral in Johannesburg, a position to which a black man acceded for the first time, and took up residence in the ghetto district of Soweto, where he witnessed one of the most convulsive stages of apartheid, with the student protests of 1976 in which more than 600 people died.

In 1977 Tutu was appointed bishop of Lesotho and, just a year later, he was appointed general secretary of the South African Council of Churches. At that time he began to openly express his support for the Black Consciousness movement and intensified his anti-apartheid activism until he became an international figure.

In 1990, after 27 years in prison, Mandela spent his first night of freedom at Tutu’s residence in Cape Town. Later, Mandela called Tutu “the people’s archbishop.” Under Mandela, Tutu was appointed chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a body created by the 1995 Law for the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation, which had the objective of bringing justice to those who were victims of segregationist policies.

“Without forgiveness, there is no future,” he said at the time. The commission’s 1998 report lay most of the blame on the forces of apartheid, but also found the African National Congress guilty of human rights violations. The ANC sued to block the document’s release, earning a rebuke from Tutu. “I didn’t struggle in order to remove one set of those who thought they were tin gods to replace them with others who are tempted to think they are,” Tutu said.

Apartheid had been imposed in South Africa in 1944 and it was President Frederik de Klerk, who died last month and a Nobel Prize winner along with Nelson Mandela, who in 1991 put an end to that system.

Tutu's career was marked by a constant defense of human rights, something that led him to distance himself on numerous occasions from the ecclesiastical hierarchy to openly defend positions such as homosexual rights or euthanasia. In 2013, launching a campaign for the rights of LGBTQ people in Cape Town, he said: “I would not worship a God who is homophobic.” Tutu coined the phrase that South Africa was “a rainbow country.”

In the last stage of his life he also often spoke out against the corruption of the new powers of South African democracy and against global problems such as climate change. In 1997, recently retired as a leader of the South African Anglican Church, he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer for which he underwent treatment, but in the following years he would suffer several relapses and other medical problems.

In 2010, Tutu announced that he was permanently retiring from public life to spend more time with his family. “The time has come to slow down, to drink tea with my beloved wife in the afternoons, to watch cricket, to travel to visit my children and grandchildren instead of attending conferences and conventions,” he said at the time.

Throughout the 1980s — when South Africa was gripped by anti-apartheid violence and a state of emergency giving police and the military sweeping powers — Tutu was one of the most prominent Blacks able to speak out against abuses. Tutu was arrested in 1980 for taking part in a protest and later had his passport confiscated for the first time. He got it back for trips to the United States and Europe, where he held talks with the UN secretary-general, the pope and other church leaders. Tutu called for international sanctions against South Africa and talks to end the conflict.

Read also: 23 South African teenagers killed in initiation rite this year

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rulesCommenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!