MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

Falklands War, May 21: UK begins landing troops in San Carlos for the definitive recapture of the Islands

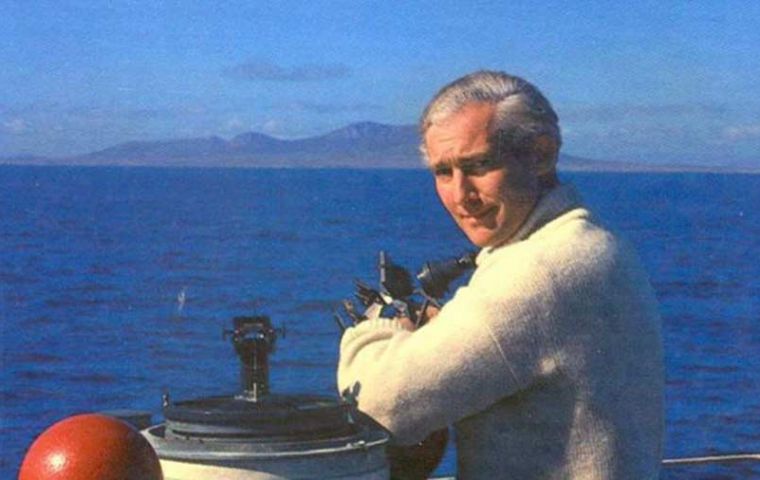

Ewen Southby-Tailyour off Pebble Island in the Falklands, 1979 (Picture: Ewen Southby-Tailyour).

Ewen Southby-Tailyour off Pebble Island in the Falklands, 1979 (Picture: Ewen Southby-Tailyour).  The iconic picture of the troops with the Union Jack, beginning their long march, yomp, to the mounts surrounding Stanley some 50 miles away

The iconic picture of the troops with the Union Jack, beginning their long march, yomp, to the mounts surrounding Stanley some 50 miles away On 21 May 1982, following the invasion of the Falkland Islands by Argentina, the UK began landing troops in East Falkland, the first stage in Operation Sutton to recapture the British Overseas Territory.

Two commanders had travelled south with the naval taskforce on board HMS Fearless – Julian Thompson commanded 3 Commando Brigade Royal Marines, which would be the landing force, and Michael Clapp was Commander of the Amphibious Task Group.

Michael Clapp would initially be in charge of the landings, with Julian Thompson taking over command as soon as the troops were safely on the beaches.

Their cabins were next to each other, and they spent the journey discussing which beaches they should use for the amphibious landings. The two commanders sought the assistance of a major and keen yachtsman, Ewen Southby-Tailyour, also on board HMS Fearless.

He had spent time serving in the Falklands and had drawn his own maps of the coastline. Major Southby-Tailyour was able to advise where the water was deep enough to allow the task force to sail close enough to release the landing craft.

He said: “At the drop of a hat I would be summoned to Julian and Mike's cabin, and it might be 3 o'clock in the morning and they'd be in their dressing gowns with a great chart of the Falkland Islands on the deck, and a great toe would descend, 'there Ewen', this was later on, when they were homing in on specific places, and I'd go away and come back in half an hour with a full lecture on that place.”

Three options were discussed: Cow Bay/Volunteer Bay, Campa Menta/Salvador or San Carlos Water.

From a military perspective, the commanders were keen to avoid beaches close to Port Stanley, because of fears that they may have been mined, or contain Argentine artillery positions that could attack as soon as they landed.

Southby-Tailyour was also keen to dissuade them from landing at Volunteer Bay, because it was home to a colony of king penguins, which he wanted to protect.

Eventually, the group decided on San Carlos. Its waters contained kelp, which Southby-Tailyour had recommended because that meant it couldn't be mined. It was deep enough to allow the larger ships into the bay, and it gave some protection from bombing from the air.

On the downside, it was more than 50 miles from Port Stanley, which meant that troops would have to travel across East Island to get to their objective. The original plan was to move troops forward in Chinook helicopters, taking out enemy positions along the way.

In the end, this would prove much more challenging following the Exocet missile attack on the container ship Atlantic Conveyor four days later, on the 25 May, in which all but one of the Chinooks was destroyed.

SAS and SBS pre-landing ops

Ahead of the landings, the Special Air Service and the Special Boat Service had both played their part in information-gathering and pre-landing operations. Just before the landings, it was discovered that there were Argentine forces at Fanning Head, at the entrance to San Carlos Water.

A Special Boat Service team with the addition of an SAS mortar detachment, using thermal imaging equipment for the first time, was able to locate and neutralize the threat. The SAS also conducted a diversionary raid at Darwin.

The plan

The landings were to happen under cover of darkness. Thompson wanted to begin at dusk, giving him the whole night to get troops and equipment on shore. Clapp wanted to use the first part of the night to bring the ships closer to shore, to protect against attacks from the sky, because the Argentines had no night-flight capability.

In the end, they came to what Thompson described as “a British compromise” – they split the difference and agreed to begin landing troops at midnight.

But, as one Falklands veteran, Ian Gardiner from 45 Commando Royal Marines, commented: “No plan survives first contact with the enemy, most don't even survive that long”, and, sure enough, the landings were delayed.

One reason for the delays was that 2 Para had not had a chance to practice boarding the landing craft, and one fell between the craft and the ship, crushing his pelvis and holding up the landings.

Brian Falkner from 3 Para, described the conditions as the landing craft began to exit from the Landing Platform Docks (LPD) HMS Fearless and HMS Intrepid and head for shore.

He said: “It was light, beautiful sunny day, and above us, jet aircraft flying around, zooming bombs down into the bay shooting up some of the ships, shooting up some of the landing craft.

”And there's this poor little landing craft, myself and the other team in there, crushed into it, I think there may have been about 40 or 50 in there – it should have only had 30 guys on board but it didn't, and it didn't have sufficient life-jackets – so with the weight and the amount of equipment that they had, if they had been hit it, we would have gone straight down.“

When the landing craft reached shore, Ewen Southby-Tailyour, who had members of 2 Para on board, had some trouble with the orders to disembark: ”We lowered the ramp, and nobody moved. “The Marines shout is 'down ramp, out troops!' and the Paras hadn't the slightest idea what we were talking about.”

He went on: “Anyway, someone in the forward end of the landing craft shouted 'Paras, go!' which I think is what you shout on an aircraft when you jump out, and they all rushed ashore, happy as sandboys.”

Despite the peril involved in landing in daylight with Argentine jets overhead dropping bombs into the bay, Michael Clapp says he was surprised at how few casualties there were on the day of the landings.

“I understood that the ships were easy targets,” he said. “Even if they weren't sunk, they would inevitably be damaged either by machine-gun fire or something.

”But luckily there was no artillery there for the Argentines to take us on and that, again, is thanks to the Special Forces, being there several days ahead,” he added.

Although the delay to the operation meant that there was no time to get all the planned supplies onto East Falkland, Operation Sutton was largely successful. But there were still huge challenges ahead.

The troops were at the wrong end of an island with no roads, and after the loss of the Atlantic Conveyor, they had only one Chinook helicopter to carry troops and equipment forward. The rest would have to walk – 'yomp' or 'tab' depending on whether you're a Royal Marine or a Para – more than 50 miles in incredibly difficult weather conditions.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rules-

-

Read all commentsFor the record, Argentina claims 649 lives lost in the Falklands conflict.

May 22nd, 2022 - 05:21 pm 0This is complete hogwash. It's thought it is more likely 1200-1500. Though could easily be more.

The Argies, as ever, have been lying about their casualties.

Ultimately the home side advantage was just too great for the invading force.

May 22nd, 2022 - 11:31 pm 0Commenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!