MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

NASA announces discovery of “significant amount” of water in the moon

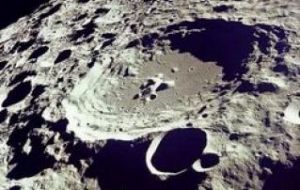

The discovery was done at the permanently shadowed crater Cabeus on the moon's South Pole

The discovery was done at the permanently shadowed crater Cabeus on the moon's South Pole It's official: There's water on the moon—and a “significant amount” of it, too, members of NASA's recent moon-crash mission, LCROSS, announced Friday. In October, NASA crashed a two-ton rocket and the SUV-size LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) into the permanently shadowed crater Cabeus on the moon's South Pole.

The crashes were part of an effort to kick up evidence of moon water (more on the LCROSS mission's moon target).

Despite disappointing many amateur astronomers on Earth, who had been expecting to see a giant plume of lunar dust and ice crystals, the moon-water mission was a success, NASA says.

The LROSS team took the known near-infrared light signature of water and compared it to the impact spectra LCROSS near-infrared recorded after the probe had sent its spent rocket crashing into the moon.

A spectrometer helps identify the composition of materials by examining which wavelengths of light they emit or absorb.

“We got good fits” for the data graphs, said Anthony Colaprete, LCROSS's principal investigator, at Friday’s press conference at the NASA Ames Research Centre in Moffett Field, California.

“We could not put other compounds [in] and generate the same fit.”

Additional support for moon water came from LCROSS ultraviolet spectrometer, which detected energy signatures associated with hydroxyl, a by-product of the break-up of water by sunlight.

The amount of lunar water kicked up by the LCROSS crashes could fill about a dozen 7.6-liter buckets, said Colaprete, adding that this is just a conservative estimate.

The confirmation of water on the moon raises the possibility that humans may one day be able to extract drinking water or breathable oxygen as well as the raw ingredients for rocket fuel from moon rocks, Michael Wargo, chief lunar scientist for Exploration Systems at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., said at the conference.

Water samples from the moon might also help shed light on the early history and evolution of the solar system, said physicist Greg Delory, a senior fellow at the Space Sciences Laboratory and Centre for Integrative Planetary Sciences at the University of California, Berkeley. “This is not your father's moon,” Delory said at the conference.

“Rather than a dead and unchanging world, it could be a very dynamic and interesting one.”

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rulesCommenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!