MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

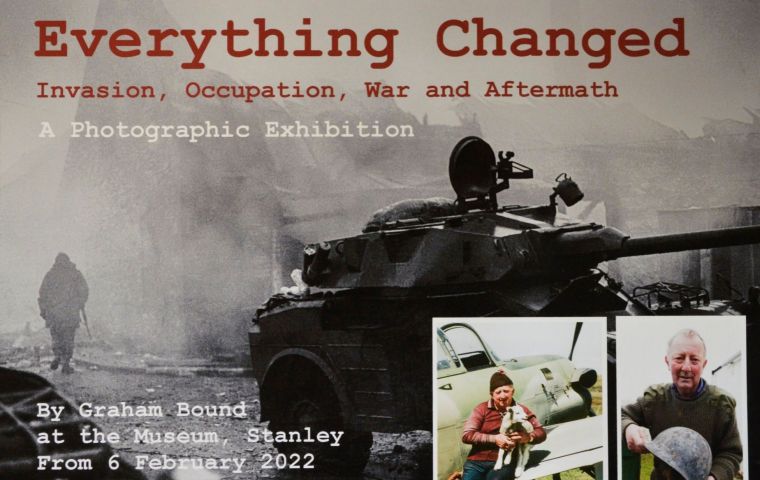

“Everything Changed”, A Falkland Islander’s Photographic Record of Invasion, Occupation, War and Aftermath

Graham experienced the war of 1982, --the exhibition is merit to that experience-- and went on to be a local correspondent for several British newspapers.

Graham experienced the war of 1982, --the exhibition is merit to that experience-- and went on to be a local correspondent for several British newspapers. By Graham Bound – “Light falls on the faces and the eyes of men. Even from a distance of four decades, we gain a glimpse of their emotions: despair, pride, exhaustion, determination, and fear”

When I conceived of this exhibition, I came up with what I thought was a catchy title: 40@40. The show is certainly that: 40 photos to mark the 40th anniversary of Argentina’s invasion and the subsequent war. But I soon realized that it did nothing to explain why my photographic record of that time deserves an audience.

Then the phrase “Everything Changed” came into my mind. That title seemed to work well, because I believe that no-one who was in the Falklands then, whether civilian or combatant, British or Argentine, was unchanged by the conflict.

A Royal Engineers NCO holds an abandoned Argentine submachine gun, next to mortar

rounds that are prepared for destruction. Credit: Graham Bound

Some suffered acute and catastrophic change through physical or mental injury, while others experienced changes to their minds and their outlook on the world that never quite went away.

In particular everything changed for the families who lost their sons, brothers, husbands, daughters, wives and sisters (because yes, women died too).

The community itself changed. London, perhaps embarrassed by the way a small group of loyal Britons had been neglected before 1982, poured money into the Islands, creating the thriving territory that exists today.

Many of the changes brought about by 1982 were for the better. But it is my sincere hope these 40 photographs remind us that the price paid was a terrifyingly intense war.

Some of the images are not particularly pleasant to look at. Interesting, yes, but not enjoyable. Fortunately, the grimmest reality is hidden in the deep black shadow of the monochrome prints. But in some of the photos, light falls on the faces and the eyes of men. Even from a distance of four decades we gain a glimpse of their emotions: despair, pride, exhaustion, determination and fear.

Defeated but not yet in captivity, Argentine soldiers ran amok through Stanley on the night of 14/15 June,

burning buildings and threatening their own officers. As British troops take control,

the Argentines become prisoners of war. Credit: Graham Bound

I was 24 years old In 1982, and the editor of the local paper Penguin News. Under Argentine occupation, publication ceased. The occupiers made it clear that the paper could only be published on their terms. There could be little argument with representatives of a regime that was known to treat its own citizens with appalling brutality. So, the final edition of Penguin News appeared days before the invasion, and the paper closed until better times returned. I was content with that.

I began recording what was going on around me in occupied Stanley. Most importantly, I took photographs. For a few days after the invasion, I walked around with my Canon cameras reasonably freely. But that soon changed. As the intensity of the conflict ratcheted-up, I took photos much more carefully, often from within buildings.

I was not spying, but it would be difficult to explain to the Argentines why I was taking photographs, as indeed it proved to be. Like so many residents of Stanley, I was arrested and interrogated. “Why were you seen taking photos on the day we arrived?” asked an aggressive army intelligence officer at the police station. He held a file with my name on it. “Because I am a journalist,” I replied.

Argentine occupation troops deploy cautiously through Stanley

early on 2 April 1982. Credit: Graham Bound

He accepted this grudgingly and warned me of consequences should our paths cross again for the same reason. Perhaps he had more serious things on his mind, such as the risk of attack. If so, he was right to be worried. Some days later the police station received a direct hit from a missile fired from a British helicopter.

Many of my 1982 photos are being seen for the first time. After the war, some made it into print in British and American publications. And some were lost. But most gathered dust for almost 40 years. They were not forgotten, though, and whenever I moved, they went with me. Then in 2021, living in London and trying to keep my spirits up during covid lockdowns (which at times reminded me of Stanley in 1982), I decided to bring the photographs back into the sunlight, restore them and create an exhibition.

By chance, I had met Alex Schneideman of Flow Photographic. Alex encouraged me to go ahead with the project and then worked with me closely. He performed wonders digitizing, restoring and printing the faded and dog-eared prints and ¬even producing prints from negatives that I had written off but, fortunately, never thrown away. These negs had a particular story.

Back in 1982, in the darkroom that I share with my friend Peter King, I mixed the developer wrongly or made some other elementary mistake. Whatever it was, the negatives emerged hopelessly “flat”. Or so I thought. I did not even bother to print them. In London, four decades later, Alex took one look at the celluloid strips and said that he could bring the images to life. He performed digital photographic magic. Seen for the first time in 40 years, these once written-off photos are some of the most dramatic in the exhibition. I am very grateful to Alex.

Creating this show cost a significant amount of money, and it would not have been possible without funding from the Friends of the Falkland Island Museum and Jane Cameron National Archives (the FIMA Friends). My thanks go to the Friends, and I hope they feel that the show justifies their generosity.

Neil Watson, of Long Island farm, holds a decaying Argentine helmet as he

recalls the days some 25 years earlier when he hauled supplies and ammunition for

troops advancing on Stanley. Credit: Graham Bound

I am of course very grateful to the staff of the Falklands Is. Museum, particularly Andrea Barlow and Tasmin Tyrrell. Thank you for welcoming the idea of an exhibition, making it part of the 40th Anniversary program, and for giving so much time and space to my project.

The next step for these photos will be taken in Britain. I am working with the Chatham Historic Dockyard Museum near London to create new prints and mount the show there. Chatham is a town closely associated with British naval history and it played its part in the events of 1982. So Chatham will be a very appropriate UK home for the exhibition.

All going well, there will also be a digital platform for the show. It is too soon to release details, but one of the UK’s main broadcasters has asked me to select photos from the exhibition, return to the locations where I shot them in 1982 and picture the same locations today. I have now done that, and it is strange but pleasing to see the remarkable contrast between the defilement of war and the peace of today. The same streets and some of the buildings remain, but in place of troops, there are people going about their peaceful business, and instead of armored vehicles, there are modern cars.

However, the actual prints in the Stanley Museum will remain there long after the exhibition has run its course. I’m sure they’ll go back into storage, which is fine: they are used to that. But I hope they will be brought back into the light from time to time to remind people of the dramatic and dangerous days of 1982; the time when Everything Changed.

(*) Graham Bound was born in the Falkland Islands and belong to a family long established in the Islands. He did part of his schooling in Uruguay's bilingual British School, and later founded the local newspaper Penguin News.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rules-

Read all commentsWhat is the inset photograph of the man with a dog standing next to the aeroplane?

Feb 12th, 2022 - 12:48 pm 0The aircraft looks more like a WWII single-engine fighter than something out of the 1982 war.

Commenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!