MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

25 Years of the Good Friday Agreement, but still a fragile Irish peace process

The secret of its success was the ultra-open border it created between the British-ruled province and the Irish republic

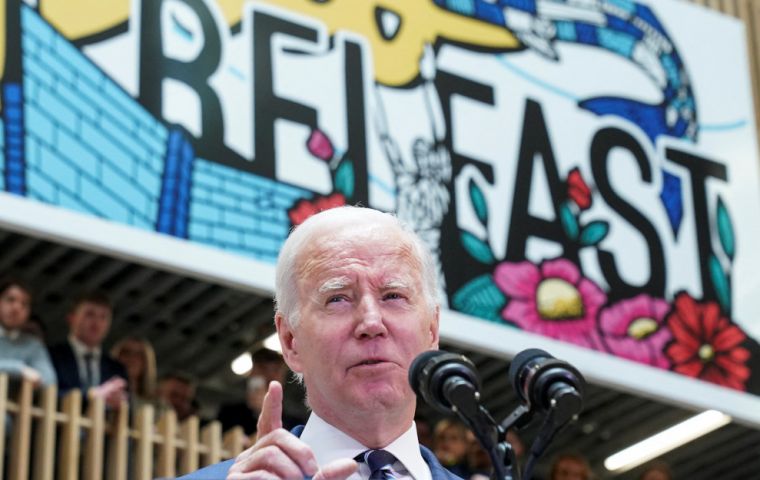

The secret of its success was the ultra-open border it created between the British-ruled province and the Irish republic U.S. President Joe Biden visited Ireland this week to celebrate an anniversary that almost didn’t happen — the 25th anniversary of the ‘Good Friday Agreement’ of 1998 that ended 30 years of killing in Northern Ireland, but it almost unraveled this year.

The ‘Troubles’ saw more than 3,000 people killed in assassinations, ambushes and bombings as the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) waged a guerrilla and terrorist war against the Protestant majority in Northern Ireland and the British army, seeking to unite the province with the Catholic-majority Republic of Ireland to the south.

Eventually the two sides fought each other to a standstill, and a 1994 ceasefire was followed four years later by the Good Friday Agreement, an intricate structure of balanced concessions, compulsory power-sharing, and of course amnesties for many people.

The Agreement was guaranteed by the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, and the European Union to which both countries then belonged. And for the next quarter-century Northern Ireland, with just under two million people, about half-Protestant, half-Catholic, enjoyed both peace and a flourishing economy.

The secret of its success was the ultra-open border it created between the British-ruled province and the Irish republic.

Catholic ‘nationalists’ dreaming of a united Ireland could live their lives as if it were true, and even claim Irish passports. Protestant ‘loyalists’ could still fly the Union Jack and pretend that nothing important had changed.

The British army was withdrawn from Northern Ireland, a new non-sectarian police was created, and most people lived more or less happily ever after. Unfortunately, this agreeable compromise depended critically on the invisibility of the ‘virtual’ border, so when Brexit came along in 2016 the whole deal was undermined.

With nationalism resurgent everywhere and the British Empire gone, an outbreak of English nationalism was quite likely, and the obvious target for it was the European Union. An ambitious journalist named Boris Johnson put himself at the head of the Brexit cause, hoping it would make him prime minister, and it did.

Johnson neither knew or cared anything about Irish politics and diplomacy, but some kind of real border with the Republic of Ireland had to reappear if the UK left the EU. He denied this fact as long as he could, but in 2019 he signed a ‘withdrawal agreement’ that put the UK-EU border in the Irish Sea, between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

This infuriated the Northern Irish ‘loyalists’, who believed they were becoming second-class British citizens. It hugely encouraged the more militant ‘nationalists’ among the Catholic population, who imagined that it was the last step before the inevitable unification of all Ireland.

And just coincidentally, the 2021 census revealed that Catholics have finally become a narrow majority of Northern Ireland’s population. So the ancient conflict began to reawaken.

Johnson then threatened to tear up the agreement, but his own Conservative Party dumped him last July over his incessant lying on this and other subjects. After the brief but deranged prime ministership of Liz Truss, the relatively calm and competent Rishi Sunak took over.

Sunak negotiated a deal with the EU in February that eases the movement of goods between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, but leaves the border in the Irish Sea. Maybe that will lull the monster back to sleep — and maybe not.

Many good people are striving to head off a collapse of the agreement, and they will probably succeed. But it’s hardly surprising that Joe Biden, of Irish Catholic descent, is starting his Irish visit in Belfast, in Northern Ireland — and that he is not planning to attend the coronation of King Charles III in London next month.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rulesCommenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!