MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

The Economist on Argentina's economy: happy-go-lucky Cristina

Earlier this year, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, Argentina’s president, proffered some advice to European governments facing recession and market panic. Its essence was “stuff the IMF and carry on spending.” It is what she and her predecessor and husband, Néstor Kirchner, have practiced since 2003. Argentina is one of only a handful of countries that refuse all dealings with the IMF. Almost a decade after it defaulted on $90 billion of debt when its economy collapsed, it still has few financial ties with the world and very little bank credit. Yet contrary to repeated forecasts of doom from orthodox economists, the economy is roaring.

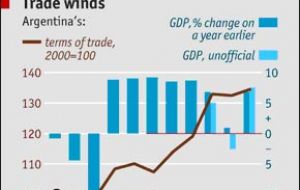

Or at least it seems to be. The numbers are a matter of dispute: in 2007 the government meddled in the statistics institute (called INDEC), and official figures now have little credibility. They show GDP as having risen by 0.9% last year, despite the world recession and a severe drought that hurt Argentina’s all-important farmers. But independent economists, who say the economy contracted by 2-2.5% last year, now forecast growth of up to 8% this year.

Like the expansion of 2003-08, this recovery is due mainly to fortunate circumstances. The drought has ended and Argentina, and especially its car industry, is benefiting from strong growth in Brazil. But the third element in the recovery is Mrs. Kirchner’s expansionary policies, which are fuelling a consumer boom. And that is where the arguments start.

When the economy began slowing, Mrs. Kirchner carried on spending: she gave loans to multinational carmakers and subsidies to keep workers in jobs. With tax revenues falling, she paid for these measures by raiding the national lottery and the pension system, which she nationalized in November 2008. In January this year the government siphoned off $6.6 billion from the Central Bank’s reserves in order to pay debt (a decision which prompted the resignation of the bank’s president, Martín Redrado). According to a senior official, these were emergency measures which saved jobs and welfare payments and the alternative, a fiscal squeeze, would have made the downturn worse.

Tax revenues are rising again and reserves have climbed to $50 billion, thanks to a healthy trade surplus (and despite the steady flight of capital from Argentina). But Mrs. Kirchner’s measures are running up hidden costs. The first is inflation. Although the official consumer-price index rose by only 11% in the year to July, the government has tacitly endorsed the much higher estimates by independent economists by granting wage increases of around 25% to workers and recently raising tax brackets by 20%.

Second, the government’s unorthodox methods have unnerved investors. Officials are completing a second swap of bonds on which Argentina defaulted in 2001-02. That ought to open the way for the government to return to the bond markets, to cover debt payments falling due in 2011. But it would have to pay a punitive interest rate: because of the government’s lack of credibility, the credit-default-swap spread on Argentine debt stands at 8.2% (similar to that for Greece). Lowering it would require the government to clean up INDEC, commit itself to a more transparent fiscal and monetary policy and re-establish ties with the IMF, says Daniel Marx, an economic consultant in Buenos Aires. The last item may be too much for the Kirchners, who like to blame the IMF for Argentina’s largely self-inflicted collapse of 2001-02.

The Kirchners have been extraordinarily lucky that their time in power has coincided with a surge in Argentina’s terms of trade (see chart). Asia’s rising demand for food has pushed up the price of exports of soybeans and other products from the bounteous pampas in relation to the price of the country’s imports. The first couple has extracted much of the farmers’ windfall in higher taxes, which they have recycled as subsidies and payments to poorer urban families.

In the late 1940s a similar policy, with similarly beneficial terms of trade, turned Juan Perón into a popular hero and his Peronist movement (to which the Kirchners belong) into the country’s dominant political force. But the Kirchners have been clumsy: their efforts to squeeze the farmers prompted a successful tax revolt in 2008 and made Mrs. Kirchner unpopular.

In an election last year the opposition deprived the Kirchners of a clear majority in the Congress. As well as a measure to reform INDEC, Congress is discussing a bill that would raise pensions by almost 50% to compensate for inflation. If it passes, it will be harder for the government to use the pension system as a piggy bank.

If world food prices were to fall suddenly, the Kirchners’ fiscal conjuring trick might blow up in their faces, setting off a spiral of devaluation and inflation. But for now their luck looks as though it will hold—at least until a presidential election next year. The opposition is fissiparous. Mrs. Kirchner’s approval ratings (though not those of her husband) are reviving in tandem with the economy. She may yet squeak through for a second term.

There is a third cost to the Kirchners’ methods. The government is proudly pursuing an industrial policy, with officials claiming the credit for persuading car firms to stay in Argentina rather than move to Brazil, and for attracting some sneaker factories. The first couple’s harassment of private businesses they dislike, price controls and protectionist measures have been less blatant than those of their friend, Hugo Chávez, in Venezuela, but in the long term they will deter investment and make the economy less efficient. Although Argentina’s economy is twice as big as Chile’s, it has attracted barely half as much foreign investment as its neighbor since 2007, according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. The doomsayers have been wrong about Argentina, but they may yet be proved right in the end.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rules-

-

-

Read all commentsTypical The Economist-style paper: a politically motivated propaganda-piece.

Aug 22nd, 2010 - 04:23 am 0The Economist says:

Aug 22nd, 2010 - 10:23 am 0“Yet contrary to repeated forecasts of doom from orthodox economists, the economy is roaring.”

And.............................

“ The doomsayers have been wrong about Argentina, but they may yet be proved right in the end.”

The Economist doesn't say:

Those“ Doomsday Orthodox Economists” are themselves..........

Argentina was doomed by “The Economist” in 2001

Argentina was doomed by “The Economist” in 2002

Argentina was doomed by “The Economist” in 2003

Argentina was doomed by “The Economist” in 2004

Argentina was doomed by “The Economist” in 2005

Argentina was doomed by “The Economist” in 2006

Argentina was doomed by “The Economist” in 2007

Argentina was doomed by “The Economist” in 2008

Argentina was doomed by “The Economist” in 2009

Argentina was doomed by “The Economist” in 2010

Argentina went through steady inflation from 1975 to 1991. At the beginning of 1975, the highest denomination was 1,000 pesos. In late 1976, the highest denomination was 5,000 pesos. In early 1979, the highest denomination was 10,000 pesos. By the end of 1981, the highest denomination was 1,000,000 pesos. In the 1983 currency reform, 1 Peso argentino was exchanged for 10,000 pesos. In the 1985 currency reform, 1 austral was exchanged for 1,000 pesos argentinos. In the 1992 currency reform, 1 new peso was exchanged for 10,000 australes. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 (1992) peso = 100,000,000,000 pre-1983 pesos.

Aug 22nd, 2010 - 10:43 am 0Annual inflation now 25%.

Fingers crossed, eh?

Commenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!