MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

How hedge funds held Argentina for ransom

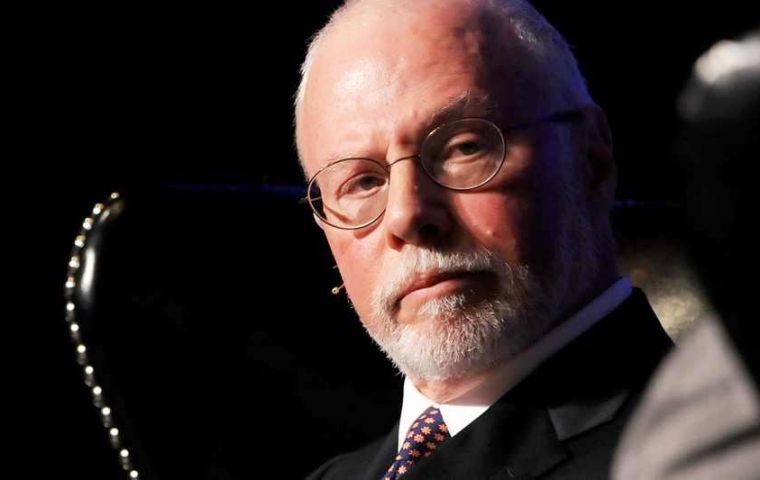

Companies involved include some of the best-known vulture funds, including NML Capital, subsidiary of Elliott Management, a hedge fund co-led by Paul Singer

Companies involved include some of the best-known vulture funds, including NML Capital, subsidiary of Elliott Management, a hedge fund co-led by Paul Singer  Singer as well as Aurelius Capital and Dart are major contributors to the Republican party

Singer as well as Aurelius Capital and Dart are major contributors to the Republican party  For a long time Argentina refused to pay holdouts and they tried all sorts of ways to change that position, including having an iconic Argentine ship seized in Ghana.

For a long time Argentina refused to pay holdouts and they tried all sorts of ways to change that position, including having an iconic Argentine ship seized in Ghana.  In 2012 Judge Thomas Griesa rules threw the game in the vulture funds’ favor, ruling Argentina had to pay them back at full value, a cost of US$4.65 billion.

In 2012 Judge Thomas Griesa rules threw the game in the vulture funds’ favor, ruling Argentina had to pay them back at full value, a cost of US$4.65 billion.

By Martin Guzman and Joseph E. Stiglitz (*) - Perhaps the most complex trial in history between a sovereign nation, Argentina, and its bondholders — including a group of United States-based hedge funds — officially came to an end yesterday (March 31) when the Argentine Senate ratified a settlement.

The resolution was excellent news for a small group of well-connected investors, and terrible news for the rest of the world, especially countries that face their own debt crises in the future.

In late 2001, Argentina defaulted on US$132 billion in loans during its disastrous depression. Gross domestic product dropped by 28%, 57.5% of Argentines were living in poverty, and the unemployment rate skyrocketed to above 20%, leading to riots and clashes that resulted in 39 deaths.

Unable to pay its creditors, Argentina restructured its debt in two rounds of negotiations. The package discounted the bonds by two-thirds but provided a mechanism for more payments when the country’s economy recovered, which it did. A vast majority of the bondholders — 93% — accepted the deal.

Among the small minority who refused the deal were investors who had bought many of their bonds at a huge discount, well after the country defaulted and even after the first round of restructuring. These kinds of investors have earned the name vulture funds by buying up distressed debt, then, often aided by lawyers and lobbyists, trying to force a settlement.

The companies involved included some of the best-known vulture funds, including NML Capital, a subsidiary of Elliott Management, a hedge fund co-led by Paul Singer, a major contributor to the Republican Party, as well as Aurelius Capital and Dart Management. NML, which had the largest claim in the Argentina case, was the lead litigant of a group of bondholders in New York federal courts.

For a long time, Argentina refused to pay the holdouts. The funds tried all sorts of ways to change the country’s position, including, at one point, having an iconic Argentine ship seized in Ghana.

Then a 2012 ruling by Judge Thomas Griesa of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York threw the game in the vulture funds’ favor, ruling that Argentina had to pay them back at full value, a cost to Argentina of US$4.65 billion. NML, for example, would get a total return of 1,500% on its initial investment, according to our calculations, because of the cheap prices it paid for the debt and because of a “compensatory” interest rate of 9% under New York law.

The ruling, which became effective in 2014, did something else: Judge Griesa issued an injunction blocking Argentina from paying anything to the creditors who had accepted the deal until it had paid the vultures in full.

The judge gave the vultures the weapon they needed: Argentina had to either pay them off or renege on the default they had negotiated, ruining the country’s credit in the future and threatening its recovery.

On Thursday, Argentina finally settled for something close to the terms that Judge Griesa set. NML Capital will receive about half of the total agreement — $2.28 billion for its investment of about $177 million, a total return of 1,180%. (Argentina also paid the legal fees for the vultures.)

This resolution will carry a high price for the international financial system, encouraging other funds to hold out and making debt restructuring virtually impossible. Why would bondholders accept a haircut if they could wait and get exorbitant returns for a small investment?

In some ways, Argentina was an outlier. It fought aggressively for the best terms from the initial set of bondholders, setting the stage for a spectacular recovery: From 2003 to 2008, until the global financial crisis intruded, the country grew 8% per year on average, and unemployment declined to 7.8% from more than 20%. In the end, the creditors who had accepted the initial restructuring got the principal value in full and even 40% more.

Most countries are intimidated by the creditors and accept what is demanded, with often devastating consequences. According to our figures, 52 percent of sovereign restructurings with private creditors since 1980 have been followed by another restructuring or default within five years. Greece, the most recent example, restructured its debt in 2012, and only a few years later it is in desperate need of more relief.

It’s common to hear the phrase “moral hazard” when looking at countries that face crushing debt, like Greece or Argentina. Moral hazard refers to the idea that allowing countries (or companies or people) to renegotiate and lower their debts only reinforces the profligate behavior that put them in debt in the first place. Better that the debtor faces disapproval and harsh consequences. But the Argentina deal reversed the moral hazard by rewarding investors for making small bets and reaping huge rewards.

Britain and Belgium have made particular kinds of vulture suits illegal. Similar legislation, with bipartisan support, stalled in Congress in 2009. Last September, the United Nations overwhelmingly approved nine principles that should guide sovereign debt restructuring. During the debate, one ambassador apologized to actual vultures — the birds — for using the term. (One of us, Martin Guzman, made presentations to both the United Nations and to the Argentine Senate, but was not paid in either case.)

Only six countries voted against, but as those are the major jurisdictions for sovereign lending (including the United States), these principles will not be very effective.

Many countries have bankruptcy laws. But there is no equivalent framework for sovereign bankruptcies, not even something remotely close to that. The United Nations has taken the lead to fill this vacuum, and as Argentina’s case proves, the initiative is more important than ever.

(*) Martin Guzman, is a research fellow at the Columbia University Business School and a senior fellow at the Center for International Governance Innovation.

(*) Joseph Stiglitz, a professor at Columbia, won the Nobel in economic science in 2001.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rules-

-

-

Read all commentsThis reminds me of some country who made its fortune with piracy, raiding, slavery (world leaders at slavery too!), opium trading, colonial imperialism, and economic bullying and cheating, to the present without interruption.

Apr 02nd, 2016 - 01:48 pm 0It seems the yankees, true bigots like their ancestors never mixing with the aboriginals except to kill ´em, also carry the same talent in their blood.

Stiglitz (who worked for CFK but violated Colombia's ethics rules in failing to report it), Guzman, and Kicillof should be rated as the Three Stooges.

Apr 02nd, 2016 - 01:50 pm 0As usual they are whingeing about nothing. The solution to their imaginary problem was solved years ago with the recognition that Collective Action Clauses should be (and now are) used consistently in sovereign debt matters. CACs have been available and used for this sort of debt for more than 100 years. You just have to be smart enough to include them when selling debt. That's a level of intelligence that escapes Stiglitz and his crybaby friends.

Argentina and Argentina alone is responsible for its debt problems. It was counseled to include Collective Action Clauses in the bond sales that led to the defaulted debt that has now become very expensive to deal with. And Argentina elected not to include CACs in that debt. Under the prevailing law, they could not make CACs retroactive, an effect that Argentina tried to gain by saying that if 93 percent agreed to a cram-down, then everybody ought to. Nope.

Stupid has its consequences. And stupid has its apologists, in the form of the corrupt Stiglitz.

----------

“...including having an iconic Argentine ship seized in Ghana....”

A: The ship was never seized. The article writer doesn't understand the meaning of seizure.

-----------

“...officially came to an end yesterday ....”

A: Nope. It's not over yet. Nobody has been paid and it looks like the 14 April deadline for payment won't be met.

Argys think its racist and piracy to ask to be paid on time and in full for contracts.

Apr 02nd, 2016 - 02:10 pm 0No wonder they'll always be considered 3rd world.

Commenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!