MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

Ozone hole: NASA's satellite confirms 20% less depletion; recovery by 2080

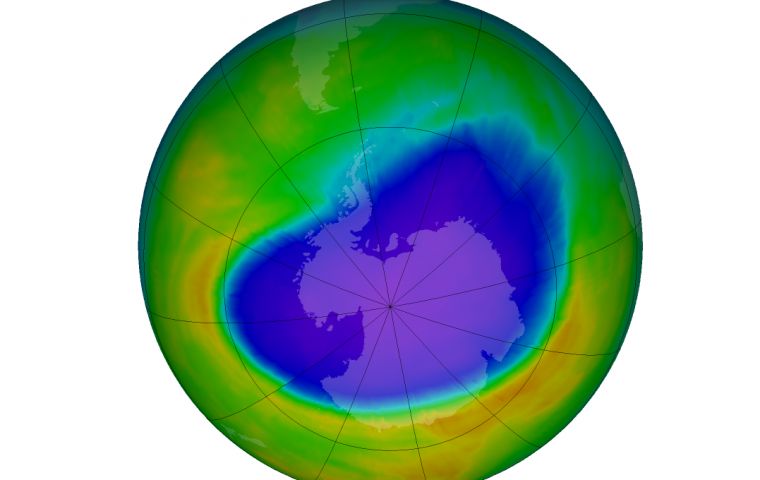

Antarctic ozone hole forms during September in the South Hemisphere winter as returning sun’s rays catalyze ozone destruction cycles of chlorine and bromine

Antarctic ozone hole forms during September in the South Hemisphere winter as returning sun’s rays catalyze ozone destruction cycles of chlorine and bromine  Scientists use data from the Microwave Limb Sounder, MLS, aboard the Aura satellite, which has been making measurements around the globe since mid-2004.

Scientists use data from the Microwave Limb Sounder, MLS, aboard the Aura satellite, which has been making measurements around the globe since mid-2004. Scientists have shown through direct satellite observations of the ozone hole that levels of ozone-destroying chlorine are declining. Measurements show that the decline in chlorine, resulting from an international ban on chlorine-containing man-made chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), has resulted in about 20% less ozone depletion during the Antarctic winter than there was in 2005, the first year that measurements of chlorine and ozone during the Antarctic winter were made by NASA's Aura satellite.

CFCs are long-lived chemical compounds that rise into the stratosphere, where they are broken apart by the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation, releasing chlorine atoms that destroy ozone molecules. Stratospheric ozone protects life on Earth by absorbing harmful ultraviolet radiation that can cause skin cancer and cataracts, suppress immune systems and damage plant life.

Two years after the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole in 1985, nations of the world signed the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, which regulated ozone-depleting compounds. Later amendments to the Montreal Protocol completely phased out production of CFCs.

Past studies have used statistical analyses of changes in the ozone hole’s size to argue that ozone depletion is decreasing. This study is the first to use measurements of the chemical composition inside the ozone hole to confirm that not only is ozone depletion decreasing, but that the decrease is caused by the decline in CFCs.

The Antarctic ozone hole forms during September in the Southern Hemisphere’s winter as the returning sun’s rays catalyze ozone destruction cycles involving chlorine and bromine that come primarily from CFCs. To determine how ozone and other chemicals have changed year to year, scientists used data from the Microwave Limb Sounder, MLS, aboard the Aura satellite, which has been making measurements continuously around the globe since mid-2004.

The change in ozone levels above Antarctica from the beginning to the end of the southern winter – early July to mid-September – was computed daily from MLS measurements every year from 2005 to 2016. The Antarctic ozone hole should continue to recover gradually as CFCs leave the atmosphere, but complete recovery will take decades.

“CFCs have lifetimes from 50 to 100 years, so they linger in the atmosphere for a very long time,” said Anne Douglass, a fellow atmospheric scientist at Goddard and the study's co-author. “As far as the ozone hole being gone, we’re looking at 2060 or 2080. And even then there might still be a small hole.”

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rulesCommenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!