MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

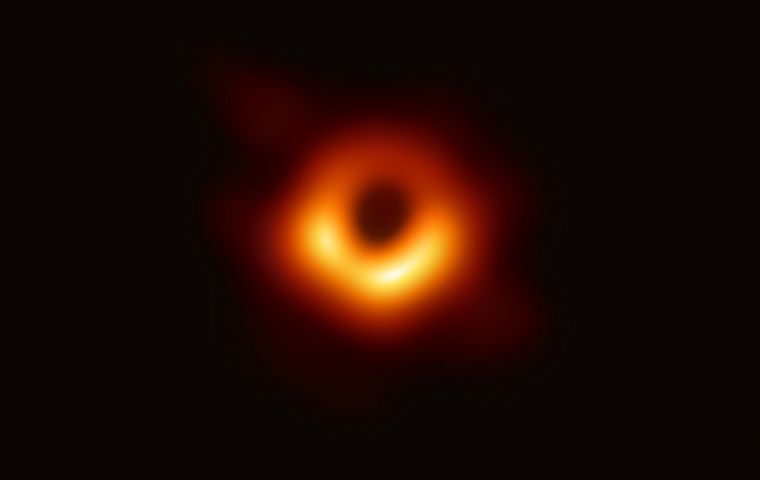

Seeing the unseeable: This is the very first picture of a black hole

Black holes are notoriously hard to see. Their gravity is so extreme that nothing, not even light, can escape across the boundary at a black hole's edge

Black holes are notoriously hard to see. Their gravity is so extreme that nothing, not even light, can escape across the boundary at a black hole's edge  “We’ve been studying black holes so long, sometimes it’s easy to forget that none of us have actually seen one,” France Córdova, director of National Science Foundation, said.

“We’ve been studying black holes so long, sometimes it’s easy to forget that none of us have actually seen one,” France Córdova, director of National Science Foundation, said.  “It’s been such a buildup,” Doeleman said. “It was just astonishment and wonder… to know that you’ve uncovered a part of the universe that was off limits to us.”

“It’s been such a buildup,” Doeleman said. “It was just astonishment and wonder… to know that you’ve uncovered a part of the universe that was off limits to us.” A world-spanning network of telescopes called the Event Horizon Telescope zoomed in on the super-massive monster in the galaxy M87 to create this first-ever picture of a black hole.

“We have seen what we thought was unseeable. We have seen and taken a picture of a black hole,” Sheperd Doeleman, EHT Director and astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., said in Washington, D.C., at one of seven concurrent news conferences. The results were also published in six papers in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“We’ve been studying black holes so long, sometimes it’s easy to forget that none of us have actually seen one,” France Córdova, director of the National Science Foundation, said in the Washington, D.C., news conference. Seeing one “is a Herculean task,” she said.

That's because black holes are notoriously hard to see. Their gravity is so extreme that nothing, not even light, can escape across the boundary at a black hole's edge, known as the event horizon. But some black holes, especially super-massive ones dwelling in galaxies’ centers, stand out by voraciously accreting bright disks of gas and other material. The EHT image reveals the shadow of M87’s black hole on its accretion disk. Appearing as a fuzzy, asymmetrical ring, it unveils for the first time a dark abyss of one of the universe’s most mysterious objects.

“It’s been such a buildup,” Doeleman said. “It was just astonishment and wonder… to know that you’ve uncovered a part of the universe that was off limits to us.”

The much-anticipated big reveal of the image “lives up to the hype, that’s for sure,“ says Yale University astrophysicist Priyamvada Natarajan, who is not on the EHT team. ”It really brings home how fortunate we are as a species at this particular time, with the capacity of the human mind to comprehend the universe, to have built all the science and technology to make it happen.“

The image aligns with expectations of what a black hole should look like based on Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which predicts how space time is warped by the extreme mass of a black hole. The picture is “one more strong piece of evidence supporting the existence of black holes. And that, of course, helps verify general relativity,” says physicist Clifford Will of the University of Florida in Gainesville who is not on the EHT team. “Being able to actually see this shadow and to detect it is a tremendous first step.”

Earlier studies have tested general relativity by looking at the motions of stars or gas clouds near a black hole, but never at its edge. “It’s as good as it gets,” Will says. Tiptoe any closer and you’d be inside the black hole — unable to report back on the results of any experiments.

“Black hole environments are a likely place where general relativity would break down,” says EHT team member Feryal Özel, an astrophysicist at the University of Arizona in Tucson. So testing general relativity in such extreme conditions could reveal deviations from Einstein’s predictions.

Just because this first image upholds general relativity ”doesn’t mean general relativity is completely fine,” she says. Many physicists think that general relativity won’t be the last word on gravity because it’s incompatible with another essential physics theory, quantum mechanics, which describes physics on very small scales.

The image also provides a new measurement of the black hole’s size and heft. “Our mass determination by just directly looking at the shadow has helped resolve a longstanding controversy,”

Sera Markoff, a theoretical astrophysicist at the University of Amsterdam, said in the Washington, D.C., news conference. Estimates made using different techniques have ranged between 3.5 billion and 7.22 billion times the mass of the sun. But the new EHT measurements show that its mass is about 6.5 billion solar masses.

The team has also determined the behemoth’s size — its diameter stretches 38 billion kilometers — and that the black hole spins clockwise. “M87 is a monster even by super-massive black hole standards,” Markoff said.

EHT trained its sights on both M87’s black hole and Sagittarius A*, the super-massive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. But, it turns out, it was easier to image M87’s monster. That black hole is 55 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Virgo, about 2,000 times as far as Sgr A*. But it’s also about 1,000 times as massive as the Milky Way’s giant, which weighs the equivalent of roughly 4 million suns. That extra heft nearly balances out M87’s distance. “The size in the sky is pretty darn similar,” says EHT team member Feryal Özel.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rulesCommenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!