MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

Physics Nobel Prize for advancing the understanding of black holes

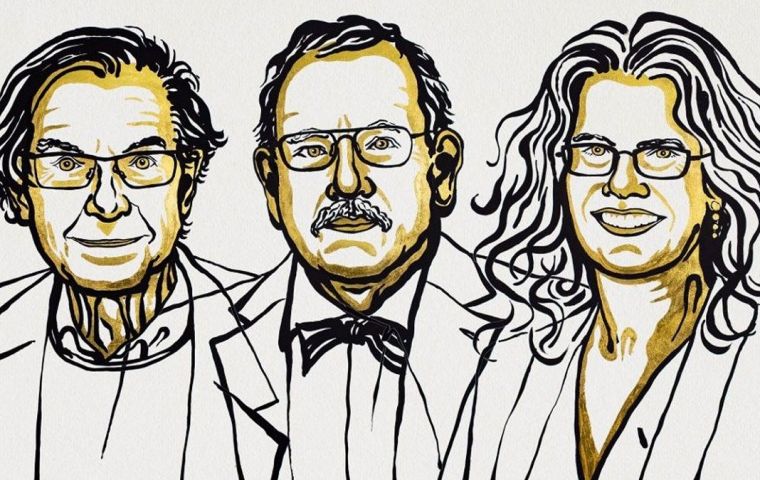

Briton Roger Penrose received half of this year's prize “for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity”

Briton Roger Penrose received half of this year's prize “for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity” Three scientists won this year's Nobel Prize in physics on Tuesday for advancing the world's understanding of black holes, the all-consuming monsters that lurk in the darkest parts of the universe.

Briton Roger Penrose received half of this year's prize “for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity”, according to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

German Reinhard Genzel and American Andrea Ghez received the second half of the prize “for the discovery of a super-massive compact object at the centre of our galaxy”, the academy's secretary-general, Goran K Hansson, said.

The prize celebrates “one of the most exotic objects in the universe”, black holes, which have become a staple of science fact and science fiction and where time even seems to stand still, Nobel committee scientists said.

Penrose proved with mathematics that the formation of black holes was possible, based heavily on Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity.

“Einstein did not himself believe that black holes really exist, these super-heavyweight monsters that capture everything that enters them,” it said. “Nothing can escape, not even light.”

Penrose detailed his studies in 1965, but it was not until the 1990s that Genzel and Ghez, each leading a group of astronomers, trained their sights on the dust-covered centre of our Milky Way galaxy, a region called Sagittarius A, where something strange was going on.

They both found that there was “an extremely heavy, invisible object that pulls on the jumble of stars, causing them to rush around at dizzying speeds”.

It was a black hole. Not just an ordinary black hole, but a super-massive black hole, 4 million times the mass of Earth's sun. Now scientists know that all galaxies have super-massive black holes.

“We have no idea what's inside the black hole and that's what makes these things such exotic objects,” Ghez said, speaking to reporters by phone shortly after the announcement.

“That's part of the intrigue that we still don't know. It pushes our understanding of the physical world.”

In 2019, scientists got the first optical image of a black hole, and Ghez, who was not involved, praised the discovery. “Today we accept these objects are critical to the building blocks of the universe,” she said.

The Nobel Committee said black holes “still pose many questions that beg for answers and motivate future research”.

“Not only questions about their inner structure, but also questions about how to test our theory of gravity under the extreme conditions in the immediate vicinity of a black hole,” it said.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rulesCommenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!