MercoPress. South Atlantic News Agency

Eighty years since the “worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”

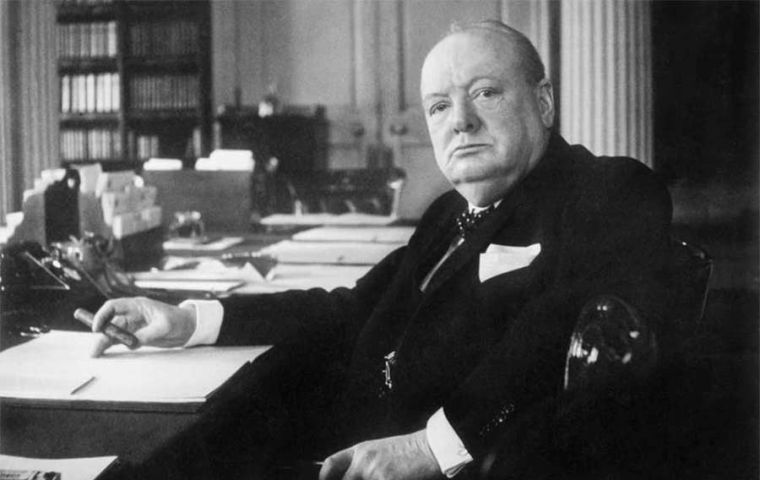

Prime Minister Winston Churchill described the defeat as the “worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”

Prime Minister Winston Churchill described the defeat as the “worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history” This month marks 80 years since Singapore, a British colony with significant strategic importance was invaded and subsequently captured by the Empire of Japan. Its loss represented the lowest point of the war in the Far East and was a matter Prime Minister Winston Churchill never really got over.

He described the defeat as the “worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”. For the defeated Commonwealth soldiers who had battled to save it, 80,000 of them immediately became prisoners of war.

The loss came about due to various unfavorable circumstances, which partly included the British military being stretched too far defending interests closer to home and the Japanese advancing throughout the Far East with a mighty rage and committed focus.

But another key reason was that of the British underestimating how and from where the Japanese attack on Singapore island would occur. A wrong assumption was made that the enemy would approach from the south – via the sea. And so, the British fortified and readied heavy weaponry, ultimately facing the wrong direction.

When the Japanese attacked from the north, after a painstakingly arduous journey through the thick jungles of Malaya, much of the island’s defenses were redundant. In defending Singapore, the British were not alone. Manning the lines were fellow Commonwealth militaries in the shape of Indian and Australian troops.

The island was also the temporary home of members of the Royal Navy who, two months earlier, had been rescued from the waters of the South China Sea following the sinking of HM Ships' Prince of Wales and Repulse. When the battle commenced on 8 February 1942, everybody took up arms.

And yet, with a force half the size of the defenders, the Japanese attackers gained the upper hand. The British surrendered within a week.

The loss of Singapore and subsequent capture of 80,000 men marked the single largest surrender in history. As said by the old Prime Minister himself, it was Britain’s “largest capitulation”.

The moment of defeat on February 15 of that year marked only the beginning of an ordeal thousands of captured men would not survive.

The prisoners, made up of entire regiments, divisions, ships’ companies, and squadrons, were to be used as slave labor in building the infamous Thai-Burma Railway and for notable landmarks such as the bridges over the River Kwai.

In many ways, their treatment at the hands of their captors overshadowed the loss of Singapore and the moment they passed into the demented responsibility of the Japanese guards.

Both physically and mentally, the scars worn by the survivors of captivity would never heal. 80 years on from the loss of the island, the anniversary is as much about those men and their experiences as prisoners of war as it is the actual fall of Singapore.

Top Comments

Disclaimer & comment rulesCommenting for this story is now closed.

If you have a Facebook account, become a fan and comment on our Facebook Page!